3I/Atlas: Anatomy of the Third Interstellar Visitor

On July 1, 2025, astronomers detected a visitor from another star system tumbling through our cosmic neighborhood.

The Fragile Visitor: Unraveling the Mystery of Interstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS

In the bone-dry expanse of Chile's Atacama Desert, under some of the clearest skies on Earth, robotic eyes scan the cosmos. This is the home of ATLAS, the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System, a sentinel built to watch for rocks on a collision course with Earth. But on July 1st, 2025, ATLAS found something else entirely. It wasn't coming for us. It was just passing through, a visitor from an unimaginable distance, moving at an impossible speed.

Astronomers quickly calculated its trajectory. With an orbital eccentricity of 1.8—far beyond the 0 to 1 range of objects bound by our sun's gravity—the verdict was clear. The object was on a one-way hyperbolic path through our solar system. It was the astronomical equivalent of a smoking gun, proving this visitor had come from interstellar space.

Initially designated C/2025 J1, it was soon given its permanent name: 3I/ATLAS. The "3I" signifies it as the third confirmed interstellar object in human history. Its discovery kicked off a global campaign to answer one question: what kind of messenger had just arrived at our doorstep?

The Case Files: ʻOumuamua and Borisov

To understand the investigation into 3I/ATLAS, we must look at the two previous visitors. They represent the two extremes of what an interstellar object can be.

1I/ʻOumuamua (2017): The "first distant messenger" was an anomaly. It was bizarrely shaped, perhaps ten times longer than it was wide, and tumbled through space like a cigar. Most mysteriously, it accelerated away from the sun with a small but persistent force that gravity alone couldn't explain. With no visible tail of gas or dust, some scientists, like Harvard's Avi Loeb, controversially suggested it could be an alien artifact—a solar sail sent from another civilization.

2I/Borisov (2019): The second visitor was the polar opposite. Discovered by an amateur astronomer, Borisov looked and acted just like a typical comet from our own solar system. It had a fuzzy coma and a tail of dust and gas. Its chemical makeup, rich in cyanide and diatomic carbon, was familiar. Borisov was the "control group"—proof that normal comets travel between the stars, which only made the memory of ʻOumuamua even stranger.

So, which would 3I/ATLAS be? Another bizarre anomaly like ʻOumuamua, or a familiar cousin like Borisov?

The First Clues and a Contradiction

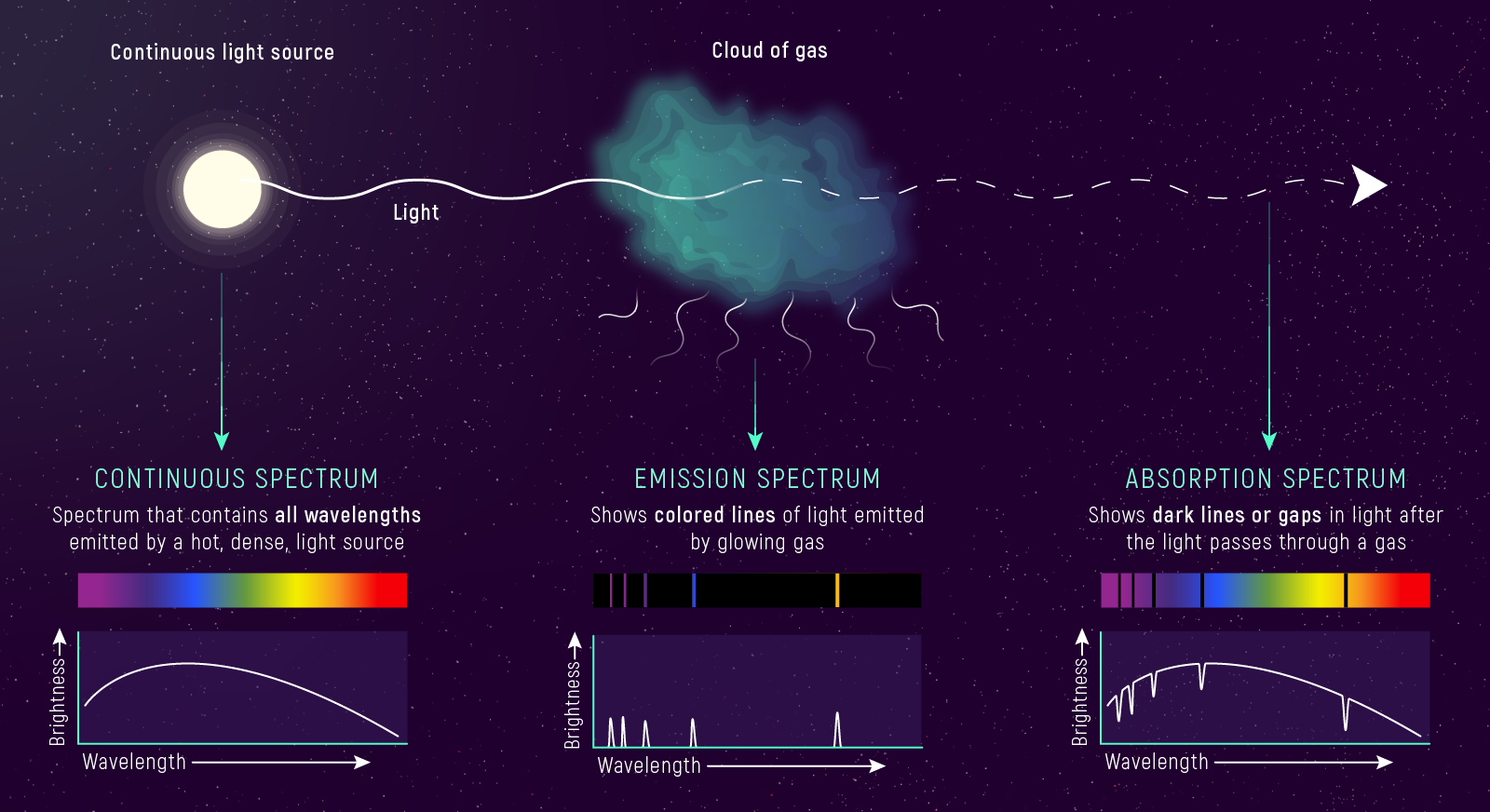

The world's most powerful telescopes turned their gaze toward the newcomer. The primary tool for the investigation was spectroscopy—the science of decoding the messages carried by light. By splitting the faint light from 3I/ATLAS into a rainbow and looking for the dark "barcode" of absorption lines, astronomers could identify the chemicals in its atmosphere with 100% certainty.

The results came in, and they were monumental. The first fingerprint found was water. The second was cyanide, a key ingredient for amino acids. The third was diatomic carbon, the molecule that gives many comets their beautiful green glow. The evidence was pointing to a clear verdict: 3I/ATLAS was a classic, active comet. It looked like we had another Borisov on our hands.

But one piece of physical evidence refused to fit. While the spectroscopy showed only a modest amount of gas being produced, telescopes saw a massive, impressive dust tail—far more substantial than the measured gas output could possibly account for. This contradiction proved that 3I/ATLAS was not a simple clone of Borisov. A deeper investigation had to begin.

A New, Alarming Hypothesis: It's Falling Apart

The strange dust tail led scientists to a new and alarming theory: what if the tail wasn't a sign of activity, but a trail of debris from a slow-motion disintegration?

Comets are not solid, monolithic rocks. They are often described as "dirty snowballs" or, more accurately, loose collections of ice, dust, and rock held together by their own feeble gravity and frozen gases. They are among the most fragile and structurally unsound objects in the solar system.

The new hypothesis suggested that as 3I/ATLAS plunged toward the sun, it was being torn apart. The intense thermal stress was causing its frozen gases to erupt, while the sun's immense gravitational tides were stretching and squeezing the nucleus, creating cracks from the inside out. The impressive dust tail wasn't being actively pushed out by gas jets; it was simply sloughing off the surface of a dying object, like stone crumbling from an ancient, weathered ruin.

The global watch had become a race against time. The investigation had revealed a fatal weakness. 3I/ATLAS was volatile, fragile, and at risk of breaking up entirely.

Countdown to Perihelion

The comet's rigid, unforgiving schedule became a cosmic drama for the world's astronomers.

- August 29, 2025: 3I/ATLAS crosses Earth's orbital path, entering the true danger zone of the inner solar system.

- September 28, 2025: The date of perihelion. This is the moment of closest approach to the sun, when the comet passes just inside the orbit of Mercury. Here, it will face the full fury of the sun's heat and gravitational forces. If it's going to break, this is when it will happen.

- October 23, 2025: Assuming it survives, the comet will make its closest pass by Earth at a safe but cosmically intimate distance of 18 million miles, offering the best views for observers.

From late October through November, 3I/ATLAS will be at its brightest. While likely too faint for the naked eye, a good pair of binoculars on a tripod should reveal it as a fuzzy, ghostly glow against the stars. It will be tracing a path through the winter constellations, passing directly through Taurus and just below the iconic Pleiades star cluster.

A Messenger's Legacy

Using data from the Gaia space observatory, astronomers have already performed a feat of celestial forensics, tracing the comet's path backward in time. Their calculations suggest that 6 million years ago, 3I/ATLAS was part of the Oort cloud of a small K2 dwarf star in the direction of the constellation Aquila. A close pass from another wandering star likely threw it out of its home system on its long journey to ours.

The arrival of 3I/ATLAS, following ʻOumuamua and Borisov, confirms a paradigm shift in our understanding of the galaxy. Our solar system is not isolated; it is part of a vast, interconnected network where star systems constantly exchange material. This has profound implications for the theory of panspermia—the idea that the building blocks of life, or even life itself, can be transported between the stars on visitors just like this one.

The story that began with the silent alarm of ʻOumuamua is now driving us to become active explorers. The European Space Agency's Comet Interceptor mission, scheduled to launch before the end of the decade, is designed to do just that: to wait in space for the next interstellar visitor and chase it down, replacing remote analysis with a direct, robotic examination. We will no longer wait for the messengers to come to us. We are getting ready to go out and meet them.