7 Details That PROVE The Pearl Harbor Story is A LIE!

The official story is that Pearl Harbor was a shocking, unprovoked attack that thrust a sleeping America into World War II.

Pearl Harbor: A Surprise Attack or a Calculated Betrayal?

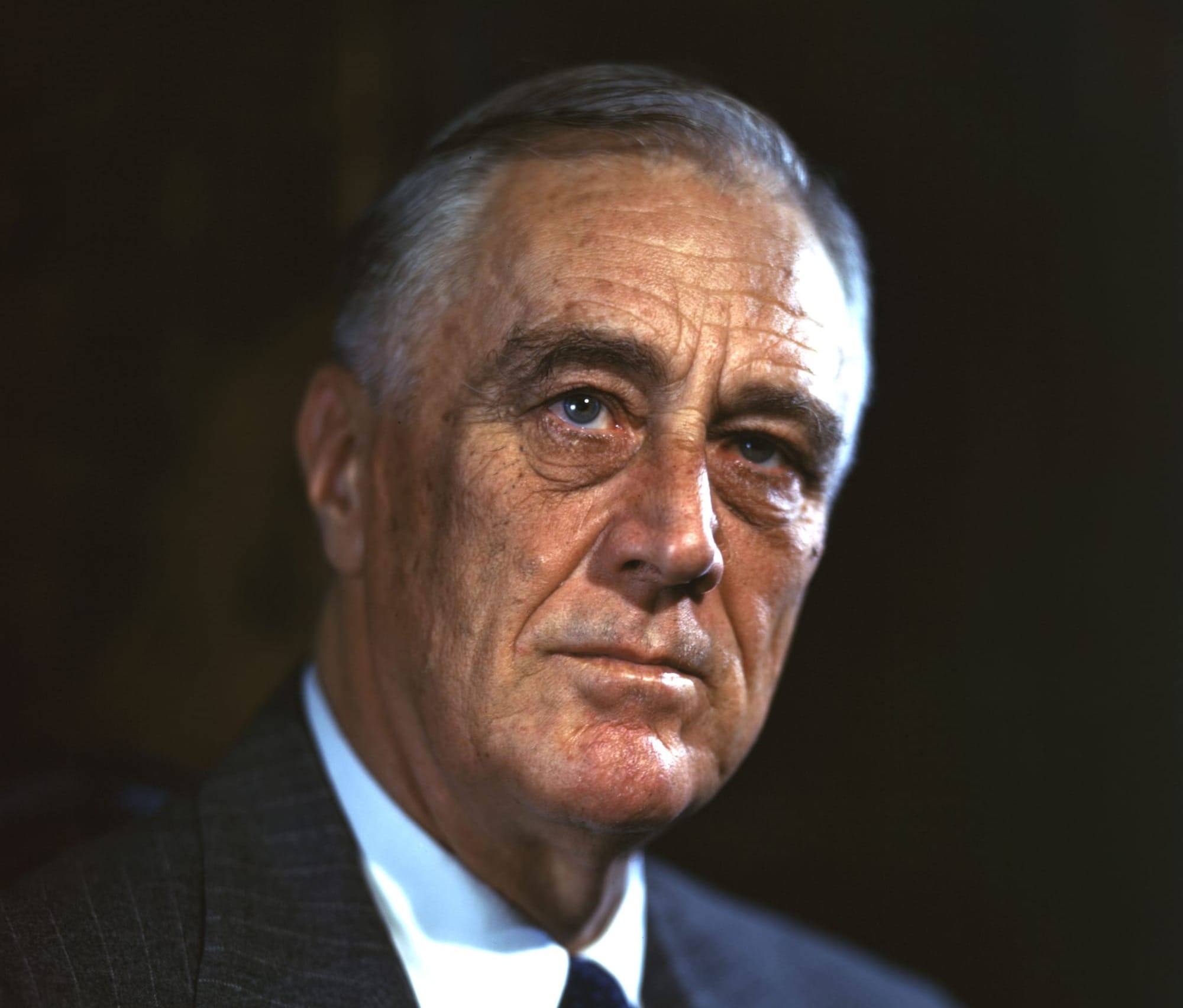

"A date which will live in infamy." With those words, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt etched December 7, 1941, into the American psyche. The official story is one we all know: a stunning and unprovoked surprise attack by the Imperial Japanese Navy on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, killing 2,403 Americans and catapulting a hesitant nation into the Second World War.

It is a story of American innocence shattered and a nation unified in righteous anger.

But for decades, a trail of declassified documents, ignored warnings, and unsettling coincidences has led historians, military insiders, and researchers to ask a deeply disturbing question: Was the attack truly a surprise? Or did key figures in the American government know it was coming—and perhaps even allow it to happen—to provide the "spark" needed to enter the war?

This is not a story of what happened on December 7th, but of the months and hours that led to it, a story that suggests the official narrative may be far from complete.

The Plan: The McCollum Memo

In October 1940, more than a year before the attack, Lieutenant Commander Arthur McCollum, a naval officer in the Office of Naval Intelligence, wrote a memorandum that has become a cornerstone for researchers questioning the official story. The McCollum Memo outlined a clear, eight-step course of action designed to provoke Japan into committing an "overt act of war" against the United States.

The memo's proposals included:

- Making arrangements with the British and Dutch to use their bases in the Pacific.

- Giving all possible aid to the Chinese government in its war against Japan.

- Sending cruisers and submarines to the Orient.

- Keeping the main strength of the U.S. Fleet in Hawaii as a direct threat.

- Instituting a complete trade embargo against Japan, cutting it off from vital resources like oil.

By early December 1941, President Roosevelt's administration had implemented every single one of McCollum's provocative recommendations. Critics argue the alignment is too perfect to be a coincidence, suggesting the eventual attack was not a surprise, but the predictable outcome of a deliberate, year-long policy of provocation.

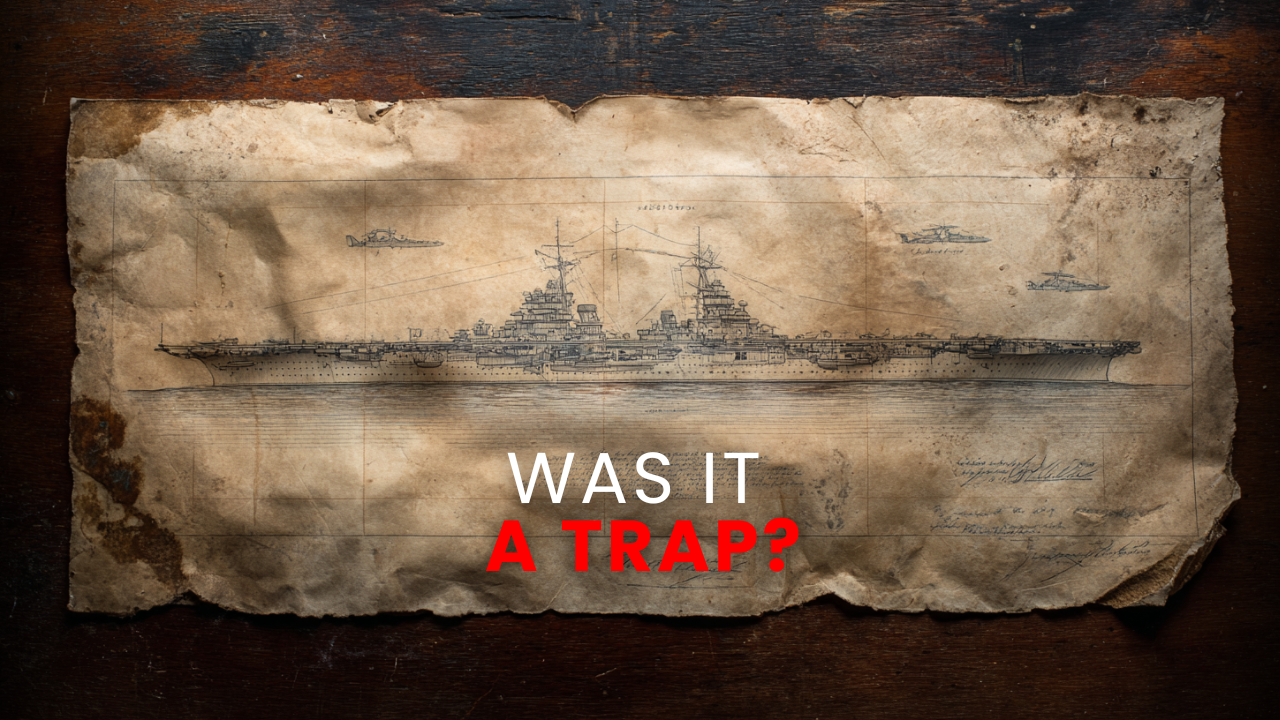

The Missing Carriers

In the naval strategy of 1941, the true measure of a navy's power was not its battleships, but its aircraft carriers. The three carriers assigned to the Pacific Fleet—the USS Enterprise, USS Lexington, and USS Saratoga—were the heart of American naval power. Sinking them would have crippled the U.S. ability to wage war in the Pacific for at least a year.

Yet, on the morning of December 7th, all three were conspicuously absent from Pearl Harbor. The Saratoga was in San Diego for repairs, while the Enterprise and Lexington had been sent on "routine" missions to deliver planes to Wake and Midway Islands. This meant the Japanese attack fell upon an impressive, but ultimately obsolete, fleet of aging battleships. The heart of America's retaliatory power remained untouched, safe in the open ocean. Was this an impossibly convenient stroke of good luck, or was it a calculated decision to sacrifice the pawns while protecting the queens?

The Ignored Warnings

The evidence becomes even more damning when we look at the specific intelligence that was available to Washington in the weeks and hours before the attack.

The "Bomb Plot" Message: Thanks to "Magic," the U.S. codebreaking operation that had cracked Japan's most secret diplomatic codes, American leaders had an open window into Japanese communications. On September 24, 1941—ten weeks before the attack—they intercepted a message from Tokyo to its consul in Honolulu. It asked for a grid map of Pearl Harbor with the exact locations of the warships at anchor. This was, in essence, a direct request for a bombing map. The significance cannot be overstated: it was a massive, flashing red light that a surprise naval air attack was being planned. This critical warning was never passed on to the commanders in Hawaii, Admiral Kimmel and General Short.

The First Shots Fired: The first shots of the Pearl Harbor attack were not fired by the Japanese at 7:55 a.m., but by the American destroyer USS Ward at 6:45 a.m. While on patrol, the Ward spotted and sank a Japanese midget submarine trying to sneak into the harbor. At 6:53 a.m., the ship's commander sent an urgent, coded message to headquarters: "We have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges upon submarine operating in defensive sea area." The presence of an enemy sub implied a mother fleet nearby. This should have triggered an immediate, base-wide alarm. Instead, due to delays and second-guessing, the warning was squandered.

The Radar Sighting: At 7:02 a.m., two Army privates at a new radar station at Opana Point detected a massive formation of aircraft—at least 50 planes—approaching from the north. They reported the huge blip to the information center, where a lieutenant on his first day as watch officer casually dismissed it, assuming it was a scheduled flight of American B-17s. He told the operators, "Don't worry about it." This was the final and best chance to prepare. An alert at that moment would have given Pearl Harbor nearly 50 minutes to scramble fighters and man anti-aircraft guns.

The Final, Fatal Delay

The ultimate evidence for many researchers lies in the final diplomatic message intercepted by "Magic" on the evening of December 6th. It was a 14-part declaration officially breaking off all negotiations. After reading the first 13 parts, President Roosevelt reportedly turned to his adviser Harry Hopkins and said, "This means war."

On the morning of December 7th, the final part arrived, instructing the Japanese ambassador to deliver the note at precisely 1:00 p.m. Washington time—7:30 a.m. in Hawaii. It was followed by an order for the embassy to destroy its code machines. This was undeniable proof of an imminent military operation synchronized to a specific time.

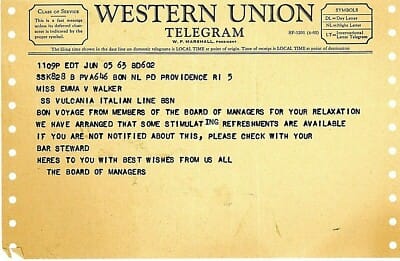

Yet, Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall claimed he was out for a morning horseback ride and couldn't be reached. When he was finally briefed, he and other top brass decided to send a warning to Pacific commands. Instead of using the secure and instantaneous telephone scrambler, Marshall made a decision that sealed Pearl Harbor's fate: he sent the most urgent warning of the war via commercial Western Union telegram.

The message arrived in Honolulu without any urgency marking. A local messenger boy set off on his bicycle to deliver it. The warning finally reached headquarters hours after the attack was over. For skeptics, the choice of a slow, unreliable telegram is the single most damning piece of evidence that the warning was never intended to arrive on time.

Was it a catastrophic series of intelligence failures and tragic coincidences? Or was it a calculated betrayal, allowing an attack to proceed in order to unite a divided country and propel it into a war that would change the world forever? The official story is written in stone, but the questions remain, buried in the archives and whispering from the wreckage at the bottom of the harbor.

This article is the companion to our full video narrative. To explore the rich context, and hear the complete story unfold, subscribe to The Purple Files Mysteries on YouTube.